The Obscure Medieval Roots of the Modern Psyche

Imagine you are in the city, riding in a car with a close friend, and he hits a pedestrian going 35 miles per hour. The speed limit is 20 miles per hour, but there are no witnesses. Your friend’s lawyer says that, if you testify under oath that he wasn’t speeding, it may save him from serious consequences. Do you lie for your friend?

If you tell him sorry, you have to be honest, you are probably pretty “WEIRD.” That is, you most likely grew up in a country which is Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (lucky you). If you’re WEIRD like me, you may be surprised to learn that, of the corporate managers across the world who were presented with this ethical dilemma, a sizable proportion outside of Western countries said that, actually, they would lie under oath to protect their friend.

Whether you’re aware of it or not, being WEIRD makes you an outlier psychologically among the world’s diverse inhabitants. Compared to the rest of humanity, Westerners are highly individualistic, self-centered, control-oriented, and analytical. We tend to focus on ourselves—our unique characteristics, achievements, and ambitions—rather than on relationships with our family and friends. Despite this narcissism, WEIRDos tend to treat people fairly, and are unusually trusting of strangers. Similarly, we think nepotism and cronyism are wrong, and we forgo numerous opportunities to further our friend’s and family’s interests.

This raises the million-dollar question: How does growing up in a WEIRD place shape your psychology?

The Catholic Church ironically created the fertile conditions necessary for the scientific Enlightenment.

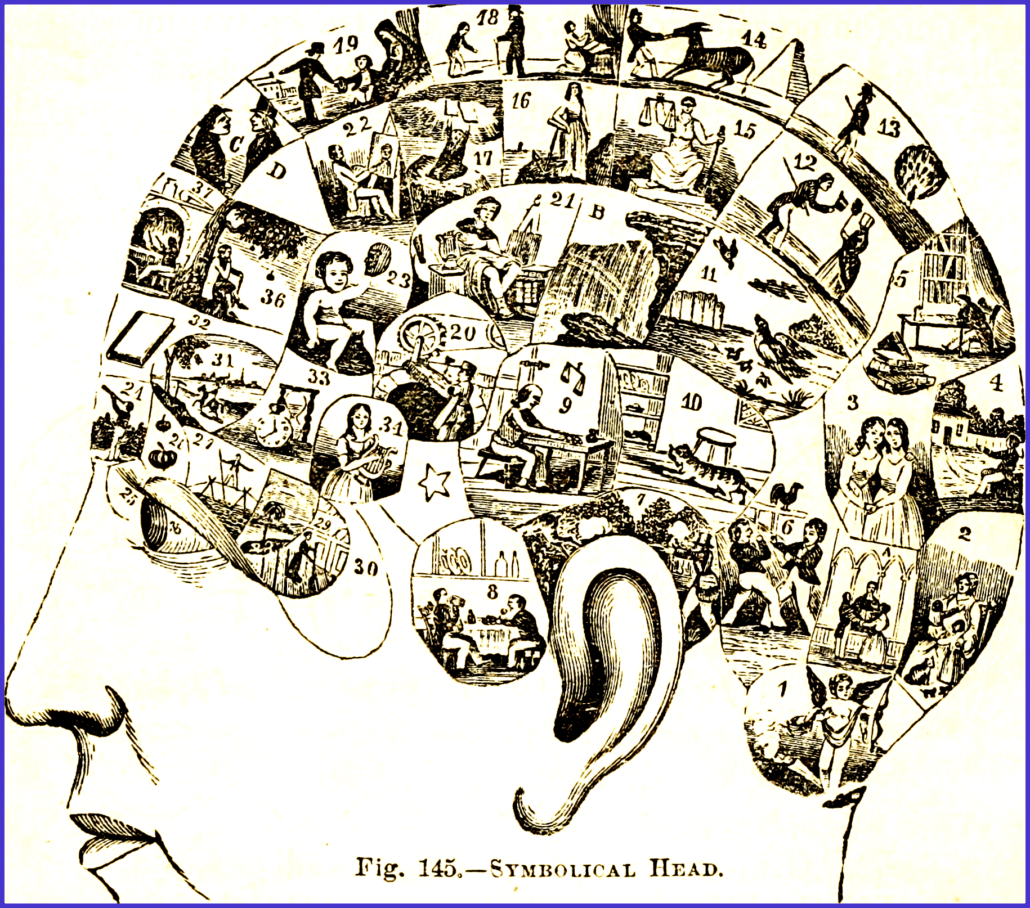

In his new book The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous, Harvard anthropologist Joseph Henrich, a champion of interdisciplinary science (he initially trained as an aerospace engineer, and has held professorships in psychology, economics, and evolutionary biology) not only explores the minds of WEIRD people but also excavates the origins of the modern world. (A tall order, I know.) The surprising conclusion that Henrich, who chairs Harvard’s department of Human Evolutionary Biology, and his collaborators have reached is that these psychological differences can be traced back to the medieval Catholic Church (the branch of Christianity that would become the Western Church). Around 1,500 years ago, it began promoting a particular set of prohibitions and prescriptions about marriage and the family. Henrich argues that this inadvertently altered people’s psychology.

“If a team of alien anthropologists had surveyed humanity from orbit in 1000 CE, or even 1200 CE, they would never have guessed that European populations would dominate the globe during the second half of the Millennium. Instead, they would probably have bet on China or the Islamic world,” Henrich writes. “What these aliens would have missed from their orbital perch was the quiet fermentation of a new psychology during the Middle Ages in some European communities. This evolving proto-WEIRD psychology gradually laid the groundwork for the rise of impersonal markets, urbanization, constitutional governments, democratic politics, individualistic religions, scientific societies, and relentless innovation. In short, these psychological shifts fertilize the soil for the seeds of the modern world.”

It’s well known that outlawing polygyny—a form of polygamy where a man has multiple wives, helps keep the worst aspects of our nature at bay (monogamy helps prevent violent uprising by armies of incels). However, counterintuitively, Henrich argues one of the most impactful of the Church’s prohibitions was the banning of cousin-marriage. This, along with the Church’s overzealous imposition of incest taboos more generally, effectively dissolved the densely interconnected clans and kindreds that roamed Western Europe (think of the prolonged political wrangling that takes place in the make-believe world of Game of Thrones—let alone all the incest). Consequently, these clans were shredded into small and independent nuclear families.

Subscribe to the Ethical Systems newsletter

This forced people, as a result, to venture outside of their close-knit communities to find their lovers to be, rather than fulfilling their obligations and duties to their extended families (which were largely assigned at birth). This incentivized people to build their own social circles and to cultivate traits that other people would find valuable and attractive (as they had to compete in the market of affection).

Henrich argues that these curbs enforced by the Catholic Church got the ball of individualism rolling, which subsequently sparked a chain of large-scale societal changes—sprouting the seeds of impartial institutions such as guilds, universities, and businesses. By the high Middle Ages, catalyzed by the Catholic Church’s social cauldron, these newly formed WEIRD ways of thinking and feeling propelled novel forms of government, whilst also accelerating innovation and the emergence of science. These self-reinforcing forces, Henrich argues, thus fuelled the rise of capitalism and liberal democracy. If Henrich’s thesis is correct, then the Catholic Church ironically created the fertile conditions necessary for the scientific Enlightenment.

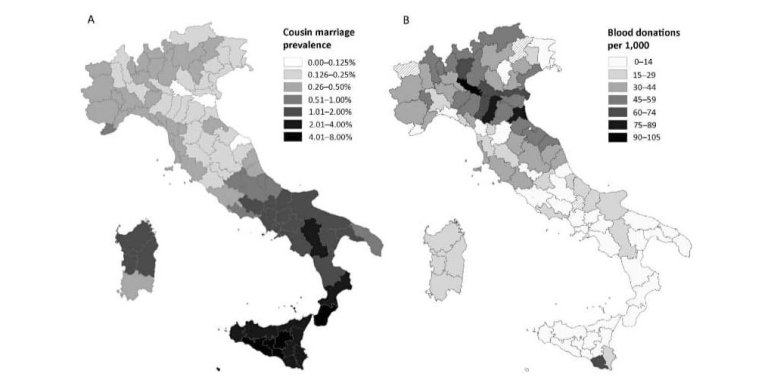

Henrich peppers his book with evidence of the lingering effects of Catholicism and Protestantism on Western minds. For example, Henrich shows that the year a country received their first dose of the Catholic Church’s family plan predicts how much their inhabitants currently respect tradition, trust strangers, and how “tight” they are culturally. Remarkably, this timing also predicts countries’ rates of voluntary blood donations as well as the amount of unpaid parking tickets that United Nations diplomats clock up in New York City. More granularly, the provinces in Italy which have the lowest rates of cousin-marriage (which serves as a proxy for Catholicism) donate much more blood on a voluntary basis.

“The cultural evolution of psychology,” Henrich writes, “is the dark matter that flows behind the scenes throughout history.” His research reveals the counterintuitive impacts of cultural practices enacted hundreds of years ago on our psychology (and even on our physiology). These are timeframes which psychologists rarely consider, and the field will probably be forced to dig a little deeper into history in light of these findings.

Henrich’s work also has clear implications for organizations whose ambitions span continents, including the inherent challenges of managing cultural differences. However, his historical insights seem most relevant to aiding international development and efforts to curb corruption. Henrich’s cultural-evolutionary perspective on modern history, for example, helps us understand how countries like Japan and China have managed to adapt rather quickly to a globalized world, whilst others, including Iran and Iraq, have struggled greatly (as large parts of the Islamic world still have intensive forms of kinship).

Evolutionary psychologists are fond of describing modern ailments as evolutionary mismatches (that is, heritable traits that were selected for in our ancestral past, which are now misaligned with the demands of the modern world). However, Henrich has identified a new strain of evolutionary mismatches: ones in our cultural-evolutionary psychology. In other words, we can’t assume that institutions that work in the Western world can just be lifted and dropped elsewhere—especially in regions where kinship ties remain strong.

“Many policy analysts can’t recognise these misfits because they implicitly assume psychological unity, or they figure that people’s psychology will shift to accommodate the new formal institutions,” Henrich writes. “But, unless people’s kin-based institutions and religions are rewired from the grassroots, populations get stuck between ‘lower level’ institutions like clans or segmentary lineages, pushing them in one set of psychological directions, and ‘higher level’ institutions like democratic governments or impersonal organizations, pulling them in others: Am I loyal to my kinfolk over everything, or do I follow impersonal rules about impartial justice? Do I hire my brother-in-law or the best person for the job?”

Henrich continues:

This approach helps us understand why “development’ (i.e. the adoption of WEIRD institutions) has been slower and more agonizing in some parts of the world than in others… Rising participation in these impersonal institutions often means that the webs of social relationships, which had once ensconced, bound, and protected people, gradually dissolve under the acid of urbanization, global markets, secular safety nets, and individualistic notions of success and security. Besides economic dislocation, people face the loss of meaning they derive from being a nexus in a broad network of relational connections that stretch back in time to their ancestors and ahead to their descendants.

Instead of pretending these cultural differences don’t exist, Henrich implores policy wonks to cater their strategies to a community’s norms and practices. If social engineers are serious about improving the human condition, they must work with, or around, such cultural-evolutionary mismatches. Just as importantly, Henrich invites social planners to consider how their interventions might alter people’s psychology centuries down the road. Trying to predict the psychological impacts of these awesome forces would be wise, however fallible our forecasting is. Cultural evolution can, after all, be quite unpredictable. Who knows which weird place it might take us to next?

Max Beilby is a business-psychology practitioner working in the banking industry. He also runs the blog Darwinian Business, which explores business from an evolutionary-psychological perspective, and more.

This article was adapted from a post on Darwinian Business.