World Cup Abuses Led Qatar to Change Labor Laws, But More Protection Is Needed

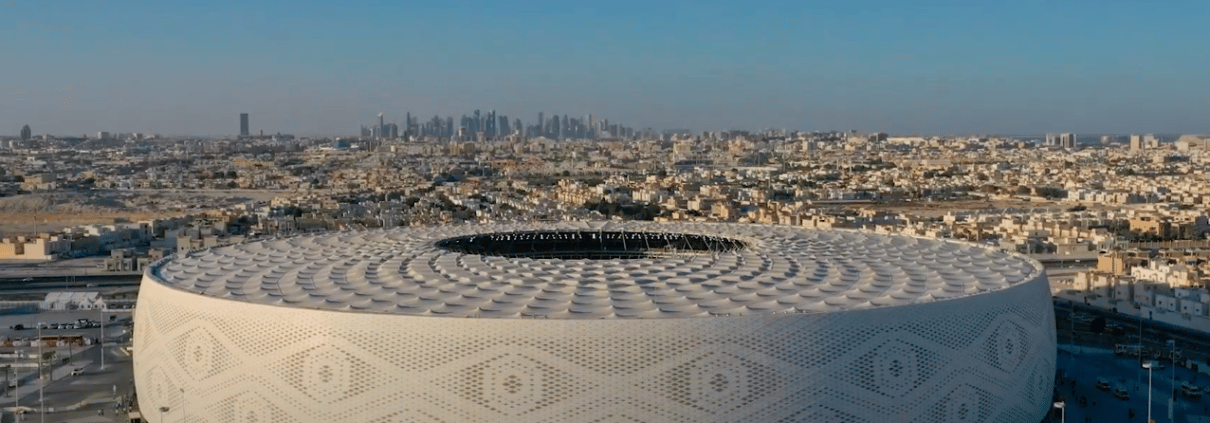

More than a million migrant construction workers, mostly young men from destitute communities in South Asia, have spent more than a decade building eight gleaming new stadiums for the World Cup in Qatar, as well as roads, hotels, a new rail line, and other facilities. This construction is part of the estimated $200 billion the Qataris are spending to host the World Cup, by far the most money ever invested by hosts of any international sporting event.

This investment is even more extraordinary for a tiny country with barely more than 300,000 citizens. The other 90 percent of the people living in Qatar are migrants from around the world. Some are well-paid professionals—doctors, lawyers, accountants, and money managers. At the other end of the economic spectrum are construction workers, and it is their treatment that now deserves attention.

Eliminating worker-paid recruitment apparently is not on the emir’s to-do list.

Construction workers in the Gulf are assigned backbreaking jobs, and they toil in suffocating heat. Many suffer heat strokes and heart attacks. Job sites often lack proper safety equipment and protocols. Estimates of the number of workers who have died on the job vary widely and run as high as 6,500. It is impossible to determine a hard number because the government refuses to collect the necessary information.

Worldwide interest in the World Cup drew attention to Qatar’s labor practices and prompted a degree of reform by the country’s government. It reduced residential crowding in worker camps, instituted a minimum wage, and lifted restrictions on those who wish to change employers. These are meaningful changes which are unprecedented in the Gulf region.

But one significant economic hardship remains. As is true throughout the Gulf, migrant construction workers in Qatar are forced to pay fees charged by recruiters in their home country, as well as the cost of their transportation, a cumulative amount that often necessitates laborers taking out high-interest loans. These debts, which can equal a year’s wages, make migrant workers more vulnerable to exploitation by employers. Ending worker-paid recruitment, which in most of the rest of the world is treated as a cost of doing business borne by employers, is long overdue.

But the Emir of Qatar, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, believes his country has already done enough to improve the lot of the migrant work force. He recently lashed out at critics, complaining that they are waging an “unprecedented campaign” against Qatar and questioning the “real reasons and motives behind this campaign.” Eliminating worker-paid recruitment apparently is not on the emir’s to-do list.

A report published earlier this year by the NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights, which I direct, describes the existing worker-funded recruitment system in detail. It explains that “while Qatari law formally prohibits this system, the government generally continues to tolerate it.”

The report also outlines the way forward. First, the government needs to revise the law to make it abundantly clear that every employer is responsible for paying all recruiting costs. To enforce this law, the government needs to expand inspections of employers and penalize companies that fail to comply. In public contracts, state agencies need to categorically reject any bids that do not include a line item for recruitment.

Subscribe to the Ethical Systems newsletter

The U.S. government has an opportunity to help promote this reform agenda. In 2018, Qatar agreed to expand and modernize the al Udeid Air Base in Qatar. This facility houses a base for the U.S. military’s Central Command and is the largest American military operation in the Gulf. Because the expansion is being undertaken by the Qataris, and the U.S. is only a tenant at the base, the Qatar Emiri Corps of Engineers oversees the design and construction of the expansion. Presumably, they are following the standard practice of having workers pay for their own recruitment.

The first phase of the air base construction, including new living quarters, is now nearing completion. In the next phase, the construction will add more work areas for U.S. and Qatari personnel and make improvements in the base’s gates and defense network, as well as its airfield operations, such as air traffic control.

If this work were being done by the U.S. government at any other overseas facility, U.S. federal acquisition regulations (FAR) would apply and treat recruitment as a project cost, not one borne by the workers. Because the U.S. Air Force is paying a portion of the cost of this base expansion, and overseeing some aspects of the project, the U.S. government should insist that FAR rules on recruitment be applied.

The hosting of the World Cup and partnership with the U.S. to expand the Al Udeid base present unique opportunities for the government of Qatar to demonstrate its commitment to human rights and leadership in the Gulf. If it acts now to eliminate worker-paid recruitment, it will receive positive attention around the world and help bring constructive pressure for reform elsewhere in the Middle East.

Michael Posner is the Jerome Kohlberg professor of ethics and finance at NYU Stern School of Business and director of the Center for Business and Human Rights. Follow him on Twitter @mikehposner.

Lead image: Screengrab via Billion Dollar Builds / YouTube

Reprinted with permission from Forbes.