Is There a Problem with Meaningful Work?

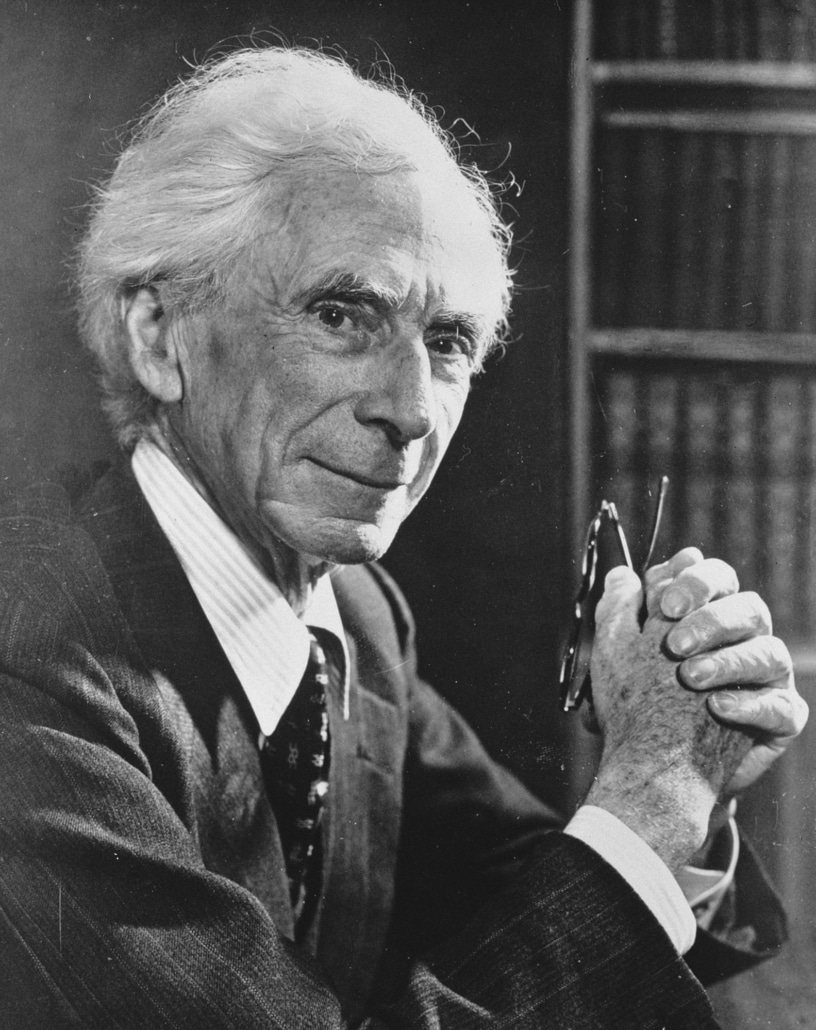

The eminent philosopher Bertrand Russell, who died exactly 50 years ago at the impressive age of 97, once penned a polemic lauding laziness. Beginning on a humorous note—he wrote of having hopes that, after reading his essay, the leaders of the YMCA would “start a campaign to induce good young men to do nothing”—Russell went on to underline the gravity of what he was proposing. “I want to say, in all seriousness, that a great deal of harm is being done in the modern world by belief in the virtuousness of work,” he wrote, “and that the road to happiness and prosperity lies in an organized diminution of work.” The eight-hour work day, he argued, should be halved. “If the ordinary wage-earner worked four hours a day,” he wrote, “there would be enough for everybody and no unemployment—assuming a certain very moderate amount of sensible organization.” Yet, far from diminishing from life, work today has instead permeated it to an alarming degree.

At least that’s what the practical philosopher and entrepreneur, Andrew Taggart, claims. Taggart, according to his bio, spends his days philosophizing with executives, entrepreneurs, and venture capitalists about the nature of a good life. Not long ago, he asked readers of the online magazine Aeon to imagine a world in which the concept of a life outside work had been expunged from cultural memory. “In this world,” he wrote, “eating, excreting, resting, having sex, exercising, meditating and commuting—closely monitored and ever-optimised—would all be conducive to good health, which would, in turn, be put in the service of being more and more productive.” This is no vision of some unlikely dystopia but more like something out of Black Mirror, “unmistakably close to our own,” Taggart wrote, one on the “verge of total work’s realization.”

“Total work” is a term Taggart borrowed from Leisure: The Basis of Culture, a 1940 book by German philosopher Josef Pieper. Total work, for Pieper, was the process of transforming humans into pure workers—people for whom “the idea of ‘work’ has invaded and taken over the whole realm of human action and of human existence as a whole.” The pure or total worker isn’t necessarily the person who often feels overworked. The life or attitude of this person, Taggart wrote, can best be seen in their routines, in the “everyday way in which he is single-mindedly focused on tasks to be completed, with productivity, effectiveness and efficiency to be enhanced.” The burden of the total worker is feeling like you can never quite leave work at work. Thoughts of missed opportunities nag constantly. The potential for maybe being lazy, for not being as productive as possible, arouses feelings of guilt. Leisure time can seem undeserved. It is the unoptimized life, in other words, that is not worth living.

In Aeon, Taggart tried to show how unwise this statement is, asking, in the title of his article, “If work dominated your every moment would life be worth living?” The natural reply is, of course, no. Yet a world of total work—“defined by ceaseless, restless, agitated activity”—could very well arrive fully, Taggart suggested, if our nine-to-five (or longer) jobs continue to be the thing around which our lives revolve. “Each day,” he wrote, “I speak with people for whom work has come to control their lives, making their world into a task, their thoughts an unspoken burden.”

Russell’s solution to this problem was to decrease work and increase leisure.

In a world where no one is compelled to work more than four hours a day, every person possessed of scientific curiosity will be able to indulge it, and every painter will be able to paint without starving, however excellent his pictures may be…Above all, there will be happiness and joy of life, instead of frayed nerves, weariness, and dyspepsia.

In 2020, the likelihood of realizing Russell’s “diminution of work” any time soon seems unlikely. And it is easy to see signs of total work manifesting around us. For example, business leaders are increasingly recognizing that offering meaningful work to their employees drives productivity, and high-skilled workers, especially in younger demographics, are seeking work that will be fulfilling. When work is a source of significant meaning, it shouldn’t be surprising that people are willing to work more than they otherwise would as well as sacrifice potential earnings from less meaningful work.

“In terms of sheer quantity of work hours, organizations will see more work time put in by employees who find greater meaning in that work,” researchers reported in a 2018 Harvard Business Review article. Ninety percent of the workers the researchers surveyed—2,285 American professionals, across 26 industries and a range of pay levels, company sizes, and demographics—said that they’d essentially pay to have more meaning at work. “On average, our pool of American workers said they’d be willing to forego 23% of their entire future lifetime earnings in order to have a job that was always meaningful.”

I can imagine that, for Taggart, this seems ominous. Meaningful work is still work. Whatever the benefits, meaningful work can displace people’s ability to enjoy leisure for its own sake, rather than for the sake of maintaining productivity. Total work “bars access to higher levels of reality,” he wrote. “For what is lost in the world of total work is art’s revelation of the beautiful, religion’s glimpse of eternity, love’s unalloyed joy, and philosophy’s sense of wonderment. All of these require silence, stillness, a wholehearted willingness to simply apprehend.”

Arguably, though, the rise of meaningful work doesn’t have to be a step toward total work. Dedication to a meaningful job can contribute to a meaningful life. Indeed, according to recent data from the Pew Research Center, four sources of meaning reported by American respondents to a survey were universally associated with relatively higher life satisfaction—good health, romantic relationship, friendship, and career. Respondents who didn’t mention any of these four as sources of meaning had an average life satisfaction of 6.3 out of 10. Mentioning all four raises the average to 8.4. People who mentioned career—but not friendship, health, or family—averaged 7.1. “Those who mentioned their job or career rated their lives 8% higher than those who didn’t mention the topic,” according to Pew, “regardless of any other topics they may have mentioned.”

Of course, although it is possible to find meaning in work, many people, particularly those in non-management jobs and roles typically considered uncreative, do not. Pew, in other research, has found that only half of Americans are “very satisfied” with their work. Workers who are in retail, service, or manual occupations have relatively fewer benefits and lower levels of satisfaction. The good news, though, is that, even in these sorts of jobs, it is possible to carve out room for more meaning. Research shows that all work becomes “knowledge work” when workers are free make use of their experience in shaping their work. “When workers experience work as knowledge work,” according to the Harvard Business Review, “work feels more meaningful.”

Tweaking all sorts of work to be more like knowledge work is no small task. As Lea Cassar, a professor of empirical economics, and Stephan Meier, a professor of business management, wrote in a 2018 paper, “Seeking to create meaning through a change in mission or job design may require some fundamental changes in the organization.” Companies interested in making these sorts of changes could benefit from an experimental approach to culture, which we, at Ethical Systems, very much support. Broadly, the end goal would be to foster a “benevolence climate,” one that supports multiple stakeholders inside and outside the organization, which is associated with positive employee attitudes and behaviors. By contrast, perceptions that the organization has a “self-interest climate,” where it’s every person for him or herself, are associated with negative attitudes and behaviors.

To close with a quote from Russell’s “In Praise of Idleness,” “Good nature is, of all moral qualities, the one that the world needs most, and good nature is the result of ease and security, not of a life of arduous struggle.”

Brian Gallagher is Ethical Systems’ Communications Director. Follow him on Twitter @BSGallagher.