The Psychological Cost of Companies Sounding Ethical for Money

In Star Wars Han tells Leia, after rescuing her from execution, “Look, I ain’t in this for your revolution and I’m not in it for you, princess. I expect to be well paid. I’m in it for the money.” Later, Luke tells him, as fighters are boarding their X-Wings to attack the Death Star, “You know what’s about to happen, what they’re up against. They could use a good pilot like you—you’re turning your back on them.” Han, gathering his cash unmoved, says, “What good’s a reward if you ain’t around to use it?” You remember what happens next, of course: Han shows up to the fight in the Millennium Falcon at the crucial second to save Luke and the rebellion. He risked it all—his money, his life—because of an apparent change of heart. What truly mattered wasn’t saving his skin but something more sacred—being there for his friend for a chance at defeating the Empire.

I thought of Han’s heroism after reading a recent study in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. “Values are deemed sacred when people state an unwillingness to compromise them, especially in exchange for more secular values, such as economic considerations around profit and cost–benefit analyses,” write Rachel Ruttan, a social psychologist at the University of Toronto, along with Northwestern University’s Loran Nordgren. “By contrast, secular (nonsacred) values are normatively treated as fungible, and people make secular trade-offs on a regular basis, as when people make price-quality trade-offs in the supermarket.” Risk-reward trade-offs can be similarly secular: One of my favorite Han Solo lines comes when Luke, nearly whispering, says to Han, “She’s rich,” referring to Leia. “If you were to rescue her, the reward would be…” “What?” Han wants to know. “Well,” Luke says, “more wealth than you can imagine!” “I don’t know,” Han says, “I can imagine quite a bit.” Ha!

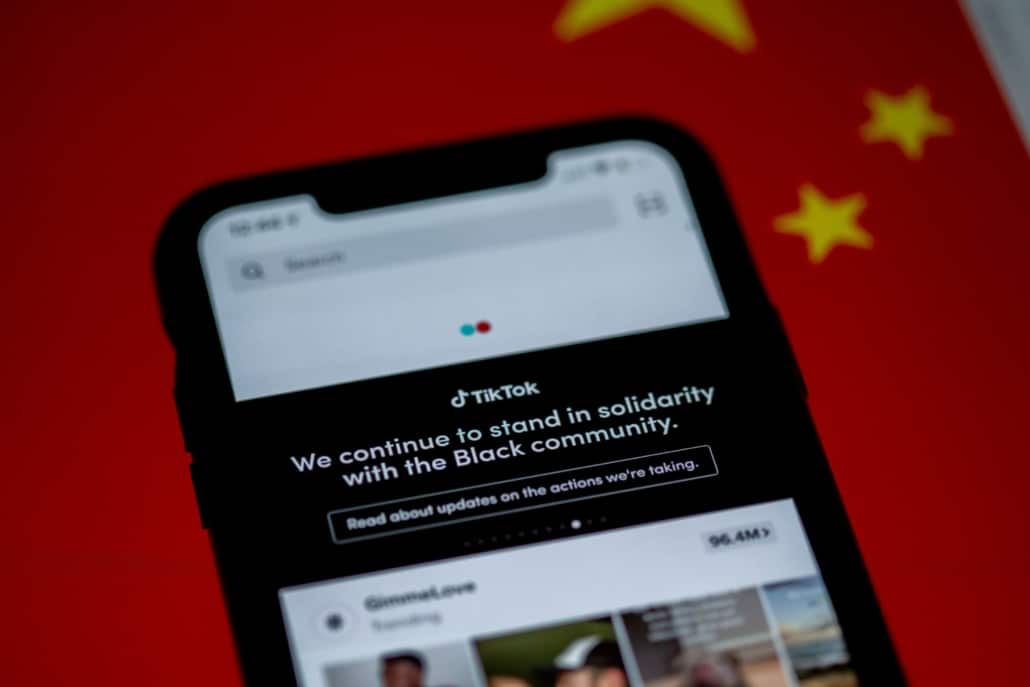

Ruttan recently did a “scrape” of the Fortune 1000 companies relevant to Black Lives Matter. “You just see very repetitive lines of text,” she said.

In their paper, Ruttan and Nordgren investigate what happens to sacred values when people or groups look to promote or advance them for tangible gain. “A fundamental feature of sacred values like environmental-protection, patriotism, and diversity is individuals’ resistance to trading off these values in exchange for material benefit,” the researchers write. “Yet, for-profit organizations increasingly associate themselves with sacred values to increase profits and enhance their reputations.”

Outlets like Quartz have called this “wokewashing” when the relevant sacred values include things like combating racism and sexism. Companies, for example, claim to care about diversity out of a sense of justice, and implement policies ostensibly on that basis—but at the same time justify diversity policies out of self-interest: Being diverse makes the brand more attractive, keeps employees happy and productive, boosts creativity, etc. A “win-win,” in other words. While Han was totally mercenary about doing something that would incidentally support galactic justice (I’m in it for the money), many corporations today want to appear to be genuine allies of social justice. And that, Ruttan and Nordgren find, has some concerning psychological effects. As they pithily put it in their paper’s title, “Instrumental Use Erodes Sacred Values.”

Ruttan, the paper’s lead author, is an Assistant Professor of Organizational Behavior and Human Resources at the Rotman School of Management. She focuses on the factors that hinder interpersonal compassion, and how companies can go wrong when they appeal to morals and values. Ruttan tries to understand what can make a policy of “doing well by doing good” backfire. In this recent paper, the argument she and Nordgren make, based on seven studies involving almost 3,000 subjects, is that being exposed to people who are looking to profit off of supporting sacred values makes those values appear less sacred. “That shifts thinking about what it is—‘Maybe diversity is great for profit,’” Ruttan told me. “That’s OK, but what we find is that that shifts the sacredness of the value because it’s now entering this sphere of profit norms.”

She started becoming curious about this phenomenon halfway through her PhD program. She was struck by how often she was coming across large corporations making messages about being green, sustainable, and diverse. “We see this a lot with the case of George Floyd lately,” she said. All of these things sparked her interest in this tendency. “I found myself having this unusual reaction that wasn’t well captured by the literature,” she said. “It was cheapening how I was thinking about things that I really deeply cared about.” She remembers looking at published research, trying to understand her own psychological reaction as a doctoral student. “If anything, the literature at the time would have made the opposite prediction—that if we get the sense that what we call our sacred values are being used in a way that’s below their purpose, we should defend against them. But I had this feeling that it was tarnishing them,” she said. “That led me to get more involved in this sphere of sacred and moral values and how they intersect with the for-profit world, as they are increasingly doing so.”

When a value that people typically regard as sacred, like environmental sustainability, enters the sphere of profit norms, it is no longer regarded as “an end in itself,” Ruttan said, something people should care about just because it’s morally important. She noted that the apparel company Patagonia actually does a good job of keeping that core value out of the profit sphere, being “very explicit that they’re willing to take on a financial cost.”

Subscribe to the Ethical Systems newsletter

Most aren’t so bold, and instead make vague and hollow value statements. “Consumers have gotten more savvy and cynical about what these mean,” Ruttan says. She notes how seemingly prosocial mission statements have proliferated and sound so similar to one another. Ruttan recently did a “scrape” of the Fortune 1000 companies relevant to Black Lives Matter. “You just see very repetitive lines of text, and if you’re exposed to these sorts of messages all the time, there is this cynicism that I think people are walking around with—‘What are you actually doing better? Are you just saying this because this is what you think I want to hear?’” She thinks that’s a large part of what’s going on with the erosion of sacred values. “If we did see this real intense commitment behind values or behind change,” she said, “we might not see this effect, absolutely.”

There seems to be an incentive, I told Ruttan, that if a company doesn’t adopt a popular, sacred value, like anti-racism, then what are consumers left to think—that they don’t support it? Companies obviously want to avoid that impression. But signaling support for a sacred value with, say, a tweet handed down from the PR department can often seem to be as far as many companies want to go. The motivation to do something meaningful—and financially costly—is lacking. “I think about this all the time in terms of what’s best,” Ruttan said. “Silence isn’t good. Especially when a clear, vivid event has happened. Neutrality doesn’t necessarily communicate the right thing, either. In general, my recommendation would be to actually think, to do more reflection before putting out something that seems very public-facing. Truly spend time thinking about how a lack of diversity and inclusion is represented internally in the organization. Don’t copy and paste other corporate tweets.”

I asked her if the idea of a “costly signal,” a term from theoretical biology, is useful here. If companies are to ward off consumers’ cynicism, shouldn’t messages about supporting sacred causes be accompanied by something that shows that a company’s commitment is real? Ruttan again noted that Patagonia does something like this, in telling people to not buy their jackets. The company also wants customers to know that it will repair damaged Patagonia apparel for free. “That’s an extreme example of a company engaging in costly signalling, but I think as people get more savvy, reading these messages and wondering what’s really behind them, more of that will be required or at least, if not a costly signal, some kind of more concrete message about what they’re actually doing,” Ruttan said. “Like, how are you changing hiring practices? Are you going to make a clear way for women and minorities to get to the top of the organization? How’re you going to change representation? Not just vague terms that sound good.”

What Ruttan thinks about all the time, and perhaps struggles a little bit with, is how to persuade people, like her business students, about the importance of values and ethics. You might say it is true that, on the whole, being a good person, someone who lives with integrity and deals honestly with others, will live a more deeply rewarding life, without regret and bitterness. A similar logic applies to organizations. It might be hard, of course, to do what’s right on occasion, because it might mean giving up something you want in the short-term, and that can be painful. But, the reasoning goes, in the end, or in the longer run, it’s personally or organizationally worth it. This sort of thinking is precisely the appeal to self-interest that raises problems.

“One of the first slides I have is about the returns on corporate social responsibility and why it makes people like you more, makes you feel better, and the company benefits,” Ruttan said. “I feel like to have legitimacy in teaching about morals and values in a business school, I have to make this case, but I don’t feel great about that. My own research shows that that’s problematic for all these reasons. But at the same time I feel that I have to communicate, to sell, why people should care about it using this language. That’s just the case. Companies need to make decisions that appease shareholders, and communications internally still have to come around to this bottom-line mentality. But I don’t know what that’s going to look like for the long run.”

We can say that time will tell, but Ruttan’s own research offers a note of caution: In the long run, using sacred values because they appear to be “good for business” may not be a sustainable strategy. That’s because doing so may only be good for business as long as people hold “sacred values” as sacred. And they won’t for long if the very practice of promoting sacred values for profit undermines the sacredness we all attach to them. As Han would say: “I have a bad feeling about this.”

Brian Gallagher is the Communications Director at Ethical Systems. Follow him on Twitter @bsgallagher.