How Corporations Should Respond to Putin’s Invasion of Ukraine

Since the end of World War II, thousands of Western-based companies have benefited from the advent of the globalized economy. They have profited from selling their products to consumers in China, India, and other far-flung markets while reducing costs by shifting manufacturing of everything from clothing to digital devices to low-wage economies. Western-based mining and oil companies have extracted raw materials in Africa and Latin America, and major U.S. and European banks have provided financing for all of these activities. This global outsourcing, which has created new opportunities for desperately poor citizens in developing countries, also has handsomely rewarded shareholders and corporate executives.

Global companies generally have thrived in this environment not only because of their ability to take advantage of advances in transportation, communications, and other technologies, but also because of a law-based international order that facilitates the enforcement of contracts, the movement of goods, and the reduction of cross-border rivalries and bullying which can disrupt trade. Now, as Vladimir Putin’s ruthless invasion of Ukraine threatens to tear down that international system, global companies have a lot to lose—and need to act.

Companies must consider whether their commercial activities are aiding the Russian military.

Governments, especially those in the U.S. and Europe, bear primary responsibility for challenging Russia’s military assault. Western governments are providing Ukraine with advanced defensive weapons and imposing financial sanctions on Moscow. But companies operating in Russia or making money from Russian-related activities also have a responsibility to act. When deciding whether to suspend or maintain those businesses relationships, senior executives need to apply criteria that go beyond standard questions about whether their companies are making a profit or complying with local law. Instead, these companies must consider whether their commercial activities are aiding the Russian military, directly or indirectly, and even if they aren’t implicated in Putin’s lethal aggression, whether they ought to cease operations in Russia as part of the broader opposition to the invasion.

Some companies have played a role, intentionally or not, in indirectly supporting the Russian military’s capacity for transportation and communications by, for example, providing spare parts for trucks, tanks, or planes. The Russian military needs trucks to transport equipment and supplies to the front lines. Therefore, it is laudable that most automobile and truck manufacturers, including Daimler Truck, Ford, and Volkswagen, have stopped production in Russia. Yet at least two tire manufacturers Pirelli and Bridgestone apparently are continuing to manufacture their products in Russia.

A much more significant example of Western participation in the Russian economy involves the production and financing of oil and gas production. Oil and gas provide roughly 40 percent of Russia’s federal budget revenue and are essential to funding Putin’s war. The U.S. and Canada have banned Russian oil and gas imports, and the U.K. is moving in the same direction. The actions of non-Russian fossil fuel companies can reinforce these bans and put meaningful pressure on Putin.

Subscribe to the Ethical Systems newsletter

Several of the largest oil companies—including BP, Shell, Exxon Mobil and Norway’s Equinor—have announced plans to divest their holdings in Russia. BP’s 20 percent share of state-owned Rosneft is the largest, worth an estimated $14 billion. But Total, the French oil giant, has been less clear about its intentions and needs to clarify its position. Recently, Shell purchased 100,000 metric tons of crude oil from Russia, reportedly at a record discount, but last week, the company reversed course and said it will no longer purchase Russian oil.

This is a defining moment in modern history.

Foreign companies without any links to the war effort also must decide whether to suspend activity in Russia. These are consumer brands, financial institutions, law and consulting firms, and other types of business enterprises. More than 300 commercial entities have decided to sever their ties to Russia. Among them are companies that have helped facilitate everyday commerce in Russia, including Mastercard, Visa, American Express, Apple Pay, Google Pay, and PayPal. Apple and Samsung have stopped selling phones and other products in Russia, as have a wide range of other consumer brands—from H&M to Nike to Airbnb and Ikea, and most recently, McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, and Starbucks.

In announcing its intention to close its 847 Russian locations, at least temporarily, McDonald’s CEO Chris Kempczinski acknowledged the difficulty of the decision, which will cost the company financially. And to its credit McDonald’s announced that it will continue to pay the salaries of its more than 62,000 local employees. But Kempczinski emphasized “our values mean we cannot ignore the human suffering unfolding in Ukraine.”

Still some highly visible companies so far have opted to stay, including Halliburton, Citi, Modelez, Subway, and Cummins. The decision to stop doing business is a difficult one—not least because tens of thousands of Russian citizens, including many who oppose Putin’s unprovoked war, will be hurt by these actions. It is important to be clear that the target is President Putin and those around him. Thus, it will make sense to carve out exceptions for companies that are providing for the essential human needs of the Russian people—medicines and baby foods, for example. But still the brutality of the invasion, and the broader threat to world order that Putin’s actions represent, should compel most companies to suspend their Russian operations.

This is a defining moment in modern history. Putin’s game-changing contempt for fundamental global norms and the inhumanity of his attacks on civilians demand that businesses help enforce the complete isolation of Russia. The goals are both to register unified opposition to Putin’s violent assault on Ukraine, and to disrupt the Russian economy as a means of exerting pressure on Putin by eroding his support among the Russian people.

Michael Posner is the Jerome Kohlberg professor of ethics and finance at NYU Stern School of Business and director of the Center for Business and Human Rights. Follow him on Twitter @mikehposner.

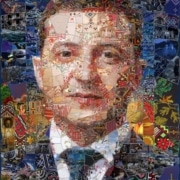

Lead image: pix-4-2-day / Flickr

Reprinted with permission from Forbes.