How Investors Can Lead the Shift Toward Stakeholder Capitalism

It’s a nightmare right now trying to measure how a company performs on environmental, social, and governance issues. As you may know, doing so involves relying on a dizzying set of intersecting quantitative frameworks, all of which struggle to balance investor demands for comparability and consistency with the reality that these “ESG” issues are highly contextual as well as industry- and geographically-specific. Any set of universal criteria will lack nuance, by definition. What’s more, the current design of these criteria prioritizes disclosure over action and certain industries over others. To take just one example of how incoherent our current state is, many ESG funds are overweight in tech companies despite pervasive concerns that those companies are helping to spread disinformation, erode democracy and mental health, and amplify political polarization.

This isn’t ideal. We are, after all, in the middle of a raging debate over how investors can better influence companies to be more ethical and sustainable. The immediate rationale for this seems to be mounting evidence that performing well on ESG metrics and criteria is broadly correlated with long-term financial performance. This news has supercharged the ESG investing movement: In the United States alone, total assets under management using sustainable investing strategies grew from US $12 trillion, at the start of 2018, to US $17.1 trillion, at the start of 2020. While this influx of capital seems to be a positive development, it is generating more confusion than clarity over the ultimate goal of all this effort. For individual companies, the causal relationship between a better ESG score, a more ethical culture, and better financial performance remains notably hazy. It’s not surprising that, rather than understanding the ESG movement as a call to rethink governance, leadership, and culture, many executives have now become obsessed with what it might take to get, more than anything else, a better ESG “score.”

All the energy dedicated to ESG investing is encouraging, but there is a pressing need to sort the signal from the noise.

Denise Hearn, author of The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Competition put this point well. “Measuring a movement meant to deprioritize shareholder returns, by investor returns, is a circular reference,” she wrote last year. “The entire raison d’etre for stakeholder capitalism is the notion that shareholder-first capitalism has failed to produce the kind of flourishing and equitable society we assumed that unbridled free-market economics would bring us. Measuring the success of stakeholder capitalism by increased profits for investors undergirds the exact paradigm it is supposedly trying to undo.”

Or, as my former colleague David Korngold, at Business for Social Responsibility, has argued, “[A]s we seek to make the transition from ‘shareholder capitalism’ to ‘stakeholder capitalism,’ we must ensure we don’t get stuck at ‘ESG shareholder capitalism’—a system that perpetuates the catastrophe of short-termism, social harms, and environmental degradation, but with better scores on ESG ratings.”

If we focus exclusively on financial performance to measure the impact of our ESG efforts, then we will subject ourselves to the very inefficiencies and manipulations that these new approaches are trying to counter. Indeed, the same market logic is also applied to any nascent corporate-governance regulation aimed at entrenching sustainable systemic change.

Many commentators are offering perspectives on whether prominent investors, such as State Street and BlackRock, are acting in good faith in their ESG approaches. Given that organizations are not individual moral beings but systems, balancing complex pressures and competing agendas, this is a near-impossible question to answer. Any firm will include both individuals who wish to invest more consciously with awareness of impacts and ethical concerns, as well as those who are bandwagon-jumpers or deep skeptics. Purity of motivation may be less useful than understanding what investor strategies are most likely to result in positive change inside corporations.

So, how can investors actually be most effective in driving positive change? Any sustained shift to stakeholder capitalism will rely on regulatory shifts as well as voluntary action, but better interactions between companies and investors are still an urgent priority. What do we know so far?

Power, legitimacy, and urgency should drive strategy. That’s what a comprehensive recent paper published by Ceres shows is optimal. For less confrontational, dialogue-driven approaches, success will be more likely if the investor outlines a clear business case and set of actions, speaks to powerful company decision-makers, and engages repeatedly over time, ideally in coordination with other investors, to demonstrate deep engagement.

For more confrontational shareholder proposals, the company is more likely to respond positively if it is facing clear reputational damage as a result of the issue in question. Investors should focus on the most visible market players, because this will drive wider responses in the industry in question. Divestment approaches will be most effective if moral and financial arguments are mutually reinforcing, and the campaign is well articulated enough to attract public and policymaker attention. For example, the campaign against private prisons now has significant momentum, with 20 U.S. states banning them so far. Many debates about whether divestment or direct engagement is “better” don’t account for these more complex considerations.

Subscribe to the Ethical Systems newsletter

Investor coalitions can be very effective. Overall, coordinated engagements that have leading and supporting investors are more successful, because they demonstrate to the company that wider social norms are shifting. Investor collaborations are more successful than individual strategies, and have other benefits such as lower research costs. Success is also more likely when the lead investor in a coalition is linguistically, socially, and culturally aligned with the target company, but the overall coalition includes other international, influential players. Other research shows that while companies that are already doing their best to implement sustainability are more likely to respond to investor pressure, the overall financial and market impact from targeting poor performers can be higher. If a company has high ownership concentration and high growth, (for example, a market-dominant social media platform like Facebook), investor pressure on ESG is less likely to succeed.

These findings further demonstrate the need to use different strategies for different firms. For poor performers, investors need to focus on the legitimacy of an ESG approach, meaning that the seniority and experience of those engaged in dialogue will be critical. For a company that already aspires to perform well on ESG issues, the messenger is less important, and the investor may just need to make clear, practical recommendations.

Reputational concerns are effective drivers of change. An influential study from 2015 shows that, overall, investor engagement is most likely to succeed with a company if it is very concerned about its reputation over the issue in question, and has the capacity to make meaningful changes inside the corporation to address the issue. It argues that reputational concerns are more prominent on environmental and social issues than governance concerns, but that improved governance is an outcome of successful engagement on environmental and social issues, because external investor influence reduces managerial myopia. Successful environmental and social initiatives, according to the paper, can enhance customer and employee loyalty, which in turn means that they are most likely to succeed in firms that are consumer-facing, brand driven, or face elevated reputational risk—companies involved in natural resource extraction would be good examples of the latter.

This suggests that reputational crises should never be wasted, and that they may be far more powerful drivers of change than gathering evidence on the business case. It also shows the difficulty of successful engagement on issues like human rights and corruption, where the company’s ability to address systemic impacts via its own initiatives may be limited.

In an intangible world, long-term thinking is the most important metric. There are many good reasons to argue that rather than focusing on improving ESG “scores,” investors should target long-term thinking, ethical leadership, and incentives. One of the key drivers of the correlation between ESG performance and long-term financial performance is the increasingly intangible nature of companies’ assets. Rather than tangible assets such as buildings, plants, and machinery, company valuations today are dominated by intangible factors such as brand, reputation, intellectual property, and patents. This means positive returns from new investments and initiatives will take longer and be less certain. Corporate leaders often understand that long-term thinking is important, but tend to default to quick fixes and status-quo biases because of pressures from quarterly reporting, transient shareholders, and high-information flows.

Investors can work to encourage long-term investments in capabilities, customer and employee loyalty, and trust, such as improved technology, good jobs, and the time and space to innovate. If investors can focus on helping companies institute a more long-term approach in general, it will be easier to put in place processes and systems that allow the benefits of ESG initiatives time to manifest.

Incentives are key. Many companies are now introducing incentives that relate to ethical or ESG issues, and many investors understand the importance of these incentive structures in driving more long-term, ethical management of our corporations. What is less often discussed is that the time horizons and approaches of the investors themselves are extremely important in driving successful engagement on ESG issues—in other words, we need patient capital, and not just patient companies.

This is critical, because employee incentives at pension funds and other long-term asset owners have themselves become significantly more short term in recent years. Investors should certainly target incentive structures in any approach designed to drive more long-term thinking, but should also look at how their own employees are assessed and rewarded.

All the energy dedicated to ESG investing is encouraging, but there is a pressing need to sort the signal from the noise. The overwhelming focus on correlating existing, highly imperfect ESG metrics with financial performance risks drowning out more promising avenues of research on how to meaningfully encourage ethical leadership, better risk-management, and a broader and longer-term approach to value creation. At Ethical Systems, we’ve been working with FCLT Global to explore some of these questions from a behavioral perspective, starting with how pension funds and other asset owners conceptualize and manage risk. We look forward to sharing more ideas as we progress.

We would very much welcome your input and collaboration!

Alison Taylor is the Executive Director of Ethical Systems. Follow her on Twitter @FollowAlisonT.

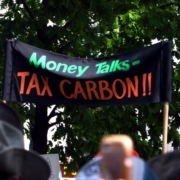

Lead image: Rafael Matsunaga / Flickr